A grumbling teddy-bear was one thing a grizzly who talked about "niggers", detested children, and coldly played women friends off against one another in order to preserve his solitude was quite another. The nation's favourite poet, lonely but loveable, was condemned as a misogynist, a racist and a porn addict. The publication of Anthony Thwaite's edition of Larkin's Selected Letters in 1992, and of my biography the following year, dramatically changed the shape of his reputation. Larkin died in December 1985, and since then Hattersley's line has come to seem less like an anomaly than a prediction.

That great bloated unsmiling accuser and his silent audience was the most depressing thing I've had to endure for a long time." "It gave me some idea of what being a writer in Russia must be like," he told his friend Judy Egerton, "arraigned in public for bourgeois formalism, counter-revolutionary determination and anti-working-class deviation. Larkin made a decent fist of seeming to find the praise embarrassing, and genuinely disliked the Hattersley programme.

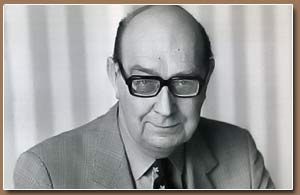

Roy Hattersley struck the single sour note, in a half-hour TV special that raked over the same sort of "faults" that Al Alvarez had found in the poems 20 years earlier: excessive pessimism, predictable gloom, narrow horizons. Faber published a collection of friendly essays, the South Bank Show did a profile (in which the only signs of Larkin himself were his hands, pudgily turning the pages of a book), and newspapers ran appreciative features about him. The last big Larkin-fest was held in 1982, and coincided with his 60th birthday.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)